What You Need To Know To Help African American Patrons Start their Genealogical Research

A librarian discusses the challenges of researching Black genealogy and offers tips to other librarians doing similar work.

Genealogy is a hugely popular hobby; once people start to investigate their families’ past, unearth information, and make connections, it’s hard to stop.

Genealogy is a hugely popular hobby; once people start to investigate their families’ past, unearth information, and make connections, it’s hard to stop.

I have been researching my personal genealogy for many years in addition to helping patrons and others with tips to conduct their own. My focus and passion is African American genealogy. This article is intended to help librarians guide African American patrons as they begin their search.

African American genealogy is essentially the same as research for other ethnic groups, though there are a few differences. These make it more challenging, but they are not insurmountable.

One of the largest challenges for African Americans who have ancestors that were enslaved is the pre-1870 U.S. Census brick wall. The 1870 census was the first in which formerly enslaved persons were listed by name. Prior to 1870, very few enslaved African Americans were listed by name in the census. There were a very few exceptions, but this went against the instructions for people completing the forms, and it isn’t clear why it happened.

Although enslaved persons were not named in the census, because they were considered property, documentation does exist. Wills and other property records can be strong sources of information.

Not all African Americans were enslaved—never assume. There were free African Americans in the United States and in other countries. However, within the United States, this was relatively rare (according to Encyclopedia.com, in 1860, free African Americans made up less than two percent of the country’s population and nine percent of the Black population). Another assumption to be wary of: Enslaved persons did not always take the name of their enslavers.

When looking at censuses taken after 1870, researchers should be aware that, depending on how records were kept locally, there might be a range of terminology used, such as Negro, colored, quadroon, octoroon, or griff (Black and Native American).

Black newspapers provide a wealth of information for genealogical research, as they focused on the lives of the Black people in a town or community. In many instances this was the only opportunity for African Americans to show their achievements and even sorrows. I was able to find a photo of a great-uncle, who I didn’t even know existed. For more information on Black newspapers, see genealogist Timothy N. Pinnick’s Finding and Using African American Newspapers (see “Further Reading").

|

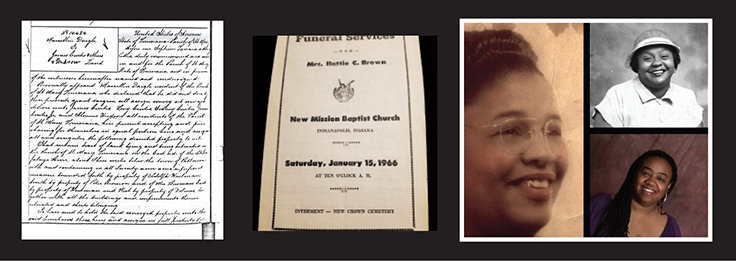

MINING PERSONAL ARCHIVES Hayes’s research has yielded plenty of information on her own family, including (l.-r.) her maternal great-grandparents’ purchase of land in 1882, a program from her maternal great-aunt’s funeral, and family photographs. Photos courtesy of Nichelle M. Hayes |

GETTING STARTED

I’ve been researching for many years and people always ask me, “How do I start?” The beginning of a research project is an invigorating time; researchers have everything to learn and no bad habits to break.

Just a few basics are necessary to get started. Researchers need only an ancestral chart, such as the one found at bit.ly/AncestralChart, and the willingness to be organized.

Patrons will need to familiarize themselves with the basic forms of genealogy, such as pedigree charts and family group sheets.

- A Pedigree Chart is a tool for genetic or genealogical research. It is similar in structure to a family tree,

but is more of a working document. - A Family Group Sheet is a record created to show the names of the mother, father, and children of a family.

Most family group records also show birth, marriage,

and death information; additional spouses (if any)

of the parents; and children’s spouses.

There are many types of records that researchers will encounter; some of the most important are census, probate, will and estate, and land and property, as well as vital (birth, marriage, death, and divorce) and pension records. Census records are taken every 10 years. However, due to privacy concerns the personal information is not revealed until 72 years after each census is taken. In 2022, the 1950 census will be available.

Some records are unique to African American genealogy. The Slave Schedules were population schedules used in 1850 (for Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, Missouri, New Jersey, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia) and 1860 (for Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Utah Territory, and Virginia). These documents listed the enslaver, number of enslaved people, age, sex, fugitive status (freedom seekers), number freed, whether and how they were disabled, and the number of houses occupied by enslaved people.

Researchers should also be aware of the Social Security Application SS-5 form, which is used to apply for a Social Security card. Roland Barksdale-Hall, library director at the Quinby Street Resource Center in Sharon, PA, has found it an incredibly useful resource. The author of The African American Family’s Guide to Tracing Our Roots: Healing, Understanding & Restoring Our Families (Amber Communication Group, 2005), Barksdale-Hall offers workshops on “How To Begin Tracing Your Roots” in the DC metropolitan area and schedules trips to the National Archives in Washington, DC, which`is responsible for maintaining the U.S. Federal Census. He was initially stumped when a patron once came to him wanting to know more about a grandparent; the only information they had was where the grandparent worked and when they died. After finding an Social Security Application SS-5 form for the individual, however, Barksdale-Hall was able to find the names of the grandparent’s ancestors. These forms are a fount of information, because they include facts such as where the individual was born, the names of their parents, where they were living at the time, and, sometimes, their occupation.

BEGINNING THE STORY

To research their genealogy, patrons should begin with themselves and work backward, toward parents, grandparents, etc. They should write down everything they know about their ancestors: name, birth and death dates, places lived and when, etc.

Advise patrons to resist the urge to start with a colorful family figure. Researchers have wasted years going down the wrong path because they didn’t start with themselves.

Once they’ve recorded their own knowledge, the next step for patrons is to conduct oral history interviews with various members of their family, starting with the elders. Attempt to confirm with documentation, if possible, what has been shared. Also, tap into family archives, photos, military discharge papers, funeral programs, scrapbooks, etc. Barksdale-Hall’s advice to a beginning genealogist or family historian is, “Begin with oral history. You are constrained by time with interviews. Talk with elders while they’re still here.”

Remind patrons to include their own history: full name (legal and nickname), when and where they were born, parents’ names (adopted, foster, etc.), where they grew up, siblings (half, step, full). Again, attempt to confirm the information with documentation. Frequently individuals have assumed something such as “I was born in Kentucky,” only to get the birth certificate and realize they were born in Ohio. Never assume! Be open to the facts. Also be open to not being able to confirm every fact. I talk frequently about settling for a “preponderance of evidence.”

When documenting the names of women, write down their birth names in addition to married names if applicable. It becomes very difficult to trace women when their last names at birth are unknown. A fellow genealogist a few years ago remarked how hard it was to track down his female ancestors. I let him know that it wasn’t an accident that women are hard to trace. Society pressures women to give up their birth (or maiden) names and consequently their historical connection to their birth families is very hard, if not impossible, to uncover.

GETTING ORGANIZED

Once the patron has all this information written down, and has cited sources such as birth certificates, death certificates, oral history, funeral programs, etc., it is time to decide what kind of organizational method they will use: folders, binders, computer files, etc. Most people will use several of these tools. Patrons can conduct research without a computer. Those willing to use a computer may find that a database program can help organize research and make sharing one’s findings easier. There are several great programs out there. Doing a cursory internet search will yield lots of great options, such as Ancestral Quest, Family Tree Maker, Brother’s Keeper, or Family Tree Builder. What’s key is that the resource is easy to use, offers customer support, and has options for exporting data.

WHERE TO FIND INFORMATION

Dr. Stanton Biddle, professor emeritus, Baruch College, New York, comes from a long line of Free People of Color who have lived in the New York area going back to 1824. When helping patrons, he starts by asking, “What part of the country is your family from, and what are your surnames?” In addition to the maternal and paternal branches of the family, each with its own surname, aunts, uncles, great-aunts, and great-uncles should all be researched fully.

As patrons gain knowledge about their surnames and where they resided, it’s important to learn about those states and the counties or parishes that comprise them. When did the state abolish slavery, or was it always a free state? When were vital statistics formerly maintained and how can they be accessed?

Biddle suggests using FamilySearch.org, which is free and provided by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS). However, some patrons may not be comfortable using Family Search because the LDS Church uses this data to perform posthumous baptism of those who did not share that faith.

Another resource that Biddle touts is Ancestry.com. While this is a subscription service, most libraries subscribe to the Ancestry library version, which is free when accessed inside the library building. (In some libraries, including mine, it was, and still is, available when buildings were physically closed because of COVID-19.)

A great deal of information has been digitized and placed online, however, not everything is online. It pays to encourage patrons to send for documents at county courthouses or state records departments. If patrons are able to go in person, a visit to the search area is very beneficial. A wonderful website that provides information about when and where documents can be accessed and how much it will cost can be found at vitalrec.com.

Barksdale-Hall believes that genealogy helps answers vital questions: “Who am I?” “Where have we been?” “Where am I going?” “Genealogy is a path to healing and empowerment,” he says. Libraries can be an essential guide along that journey. N

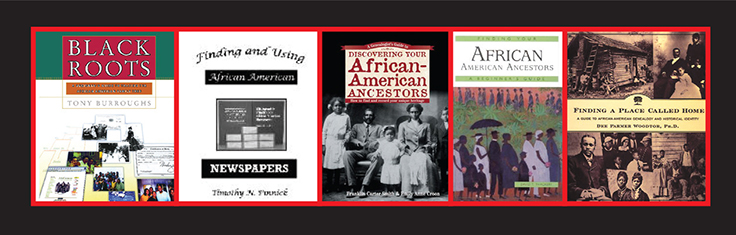

FURTHER READING

WEB RESOURCES

archives.gov/research/genealogy/startresearch/nara-resources.html

usgenweb.org

BOOKS

Burroughs, Tony. Black Roots: A Beginners Guide to Tracing the African American Family Tree. Touchstone. 2001. 464p.ISBN 9780684847047. pap. $27.99.

Pinnick, Timothy N. Finding and Using African American Newspapers. Gregath. 2008. 74p. ISBN 9780944619858. $25.

Smith, Franklin Carter & Emily Anne Croon. A Genealogist’s Guide to Discovering Your African-American Ancestors. Betterway Bks. 2002. 256p. ISBN 9781558706057.pap. $9.95.

Thackery, David T. Finding Your African American Ancestors: A Beginner’s Guide. (Finding Your Ancestors). Ancestry.com. 2001. 168p. ISBN 9781630263300. $25.95.

Woodtor, Dee Palmer. Finding a Place Called Home: A Guide to African-American Genealogy and Historical Identity. Random House Reference. 1999. 464p. ISBN 9780375405952. $34.71.

Nichelle M. Hayes, MPA, MLS, is the daughter of Sylvia & Ronzo as well as an information professional and vice-president of the Black Caucus of the American Library Association. In her spare time she blogs at thetiesthatbind.blog.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!