Organizing Your Home Library, Part 4: Weeding (Or How I Learned To—GASP!—Get Rid of Books)

In this last installment of our series aimed at helping non-librarians better organize and maintain the books in their homes, we take a look at what is sometimes a controversial subject: getting rid of old and/or outdated books.

Psst! Over here. Want to hear a shocking secret? Librarians, we oft-bespectacled lovers of the printed word, purveyors of knowledge, keepers of the world’s great literature, regularly throw away (or rather, recycle or donate, in some cases) hundreds of books every year. This practice, known in the field as deaccessioning or weeding, is a crucial part of maintaining an accurate, relevant, and useful library collection. While weeding public library books is a more pressing concern for collections that circulate and serve the needs of a community, the basic principles of the practice can help inform book lovers looking to pare down their home collections (and perhaps make room for new acquisitions).

ISN’T IT WRONG TO THROW AWAY BOOKS?!

No. In fact, keeping a book with outdated or incorrect information can be downright irresponsible. If you have an encyclopedia or guide to common diseases and prescription medicines that is more than one or two years old, chances are some of the descriptions and advice will be outdated—which can have deadly consequences. Books offering legal advice or financial guidance can similarly contain erroneous and obsolete information—even just a few years after publication. Parenting and child-rearing books from decades ago may be entertaining to browse, but most of today’s parents would hesitate before taking advice penned in the 1960s.

Some types of books and materials will have a longer—pardon the pun—shelf life than others. Fiction, poetry, plays, and books about art and music, for example, are not likely to get old or outdated. As long as the physical books hold up to repeated readings and are not falling apart, chances are you’ll never need to get rid of them. But many types of nonfiction require a vigilant eye. In most public libraries, weeding is an ongoing process. Just as librarians are continually selecting and purchasing new titles for their communities, they are simultaneously evaluating the existing collection, making sure that the offerings on the shelves are in good condition and, more important, up-to-date and accurate.

Librarians are guided by a fundamental theory, Ranganathan’s Five Laws of Library Science, which states:

First Law: Books are for use.

Second Law: Every reader their book.

Third Law: Every book its reader.

Fourth Law: Save the time of the reader.

Fifth Law: The Library is a growing organism.

Though Dr. S.R. Ranganathan (1892–1972), a mathematician and librarian from Bangalore, India, wrote these laws in 1931, they still resonate today and form the basis from which almost all librarians craft their missions, policies, and procedures.

Back in Ranganathan’s day, many university and special collection libraries chained books to the shelves to prevent theft. Think Game of Thrones’ Citadel library. The First Law acknowledges that books are first and foremost meant to be read and used by readers. They are not just pretty objects to adorn our shelves. They serve a fundamental human purpose and exist to spread knowledge. Without readers, what use are books?

The Second and Third Laws express the idea that libraries exist to serve a diverse array of readers. Not every book will be of interest to every person—and that’s OK. Librarians strive to collect as many types of books across as many subject areas and genres as they can afford in order to serve the intellectual, educational, and entertainment needs and desires of their communities.

The Fourth Law means that libraries should offer and organize their collections in ways that enable readers to find what they want as easily and efficiently as possible.

Finally, the Fifth Law gets to the heart of why weeding is so important. Most libraries are not static archives or depositories. Libraries are continually growing and evolving, keeping pace with the needs of their communities. This means removing outdated, erroneous materials to make room for new and updated works.

WEEDING YOUR HOME COLLECTION

Home collections do not typically serve the needs of a large community of users, so weeding the books in your home need not mirror the more dedicated, ongoing process that happens in public libraries. But for bibliophiles who find their shelves (and desks, corners, tabletops, and bedside tables) overrun with teetering piles of books may decide it’s time to do a bit of pruning. So what are the best practices and guidelines for getting rid of outdated books? How old is too old for informational works?

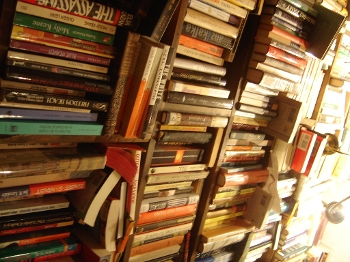

|

Tightly packed shelves damage books and make findability difficult. Photo courtesy of Flickr user Paull Young. |

One of the most popular methods for determining what books should be removed and how often is CREW, which stands for Continual Review, Evaluation, and Weeding. The CREW method offers a mix of objective and subjective criteria that helps librarians determine how quickly specific types of materials become outdated. Book lovers with very large collections and/or those who want to take a deep dive into the nitty-gritty aspects of this method can check out this guide provided by the Texas State Library and Archives Commission. For readers who took our guide to Dewey Decimal Classification (DDC) to heart, the Texas guide helpfully breaks down weeding criteria by DDC class.

For most folks with small to moderately sized home collections, here are some basic weeding tips:

Take a careful look at outdated reference works. If you own an old set of encyclopedias, atlases, almanacs, or other reference works that have great sentimental value, by all means—keep them! But don’t rely on the information they contain. Be especially wary of health and medicine books such as Physician’s Desk Reference; tax preparation guides and books on finances or estate planning; local or regional directories; and legal guides. These types of books should ideally be replaced every year or two. Many publishers update reference works with new editions; check online for updated versions of your favorite go-to guides. Many print directories containing local, state, or federal information are also available online—and updated much more frequently than print versions.

Consider the relevance of other nonfiction, including science, history, and the social sciences. New scientific developments on everything from the big bang to cold fusion are happening every day. And though it may seem like history remains constant, any historian will tell you that history is often written and framed by the perspectives—and colored by the biases—of the dominant culture. As more scholars and academics come into the humanities, arts, and social sciences, new narratives emerge that shed light on untold and underrepresented stories, people, and movements. Know that the history book you loved in high school may now contain outdated terminology and prejudiced perspectives.

Is it falling apart? It is perfectly acceptable to keep books in less-than-perfect condition, especially works from childhood or treasured books passed down from generations. Home collections often include dog-eared paperbacks and old texts from college with notes in the margins—those can be priceless personal artifacts of one’s own history. But if a book doesn’t have any special meaning, is no longer serving a useful purpose, and is in terrible physical condition, it may be time to put it in the recycling bin.

“Does it spark joy?” Even when a book is not outdated or falling apart, it can be helpful to use Marie Kondo’s iconic phrase to help decide whether that book still deserves a place on your shelf. Do you see yourself rereading it or loaning it to a friend in the future? Can you live without it? Perhaps you went through a crochet and knitting phase but no longer have an interest in those crafts. Consider donating the books to a local community or senior center. (But please call any potential donation sites in advance to ask about their book donation policies.)

WHAT DO I DO WITH ALL THE DISCARDED BOOKS?

Now that you’ve gone through your shelves and determined which books you can let go of, separate the discards into three piles: recycle, donate, and gift.

First, remove any books that contain outdated information or are in poor condition. Those are not suitable to donate or give to friends and family. Put them in the recycle bin.

Next, are there any books that hold special meaning for your family or close friends that you no longer wish to keep? Consider offering them to your children, siblings, or best buds before tossing out. If no one else wants it, toss it.

Finally, you should be left with perfectly fine books in good condition that you no longer wish to keep. Do not simply drop them off at your local library. Just as you have limited shelf space, so does your library. Call or email first to find out 1) if they accept book donations and 2) what kinds of books they take.

Consider charitable organizations such as Goodwill, HousingWorks, Better World Books, and Habitat for Humanity ReStores, as well as local retirement homes, homeless shelters, and community centers. Always call ahead or check their websites for donation requirements and procedure.

Looking for more tips on organizing your home library? Check out the previous installments in our series:

How To Shelve Like a Librarian

Understanding Books for Young Children

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!