Monty Python Medievalist, Funny Man, Author Terry Jones Dies at 77

Welsh actor, writer, comedian, screenwriter, film director, historian, and founder of the Monty Python comedy team Terry Jones died on January 21 at his home in London.

|

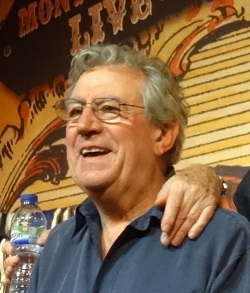

Photo by Eduardo Unda-Sanzana |

Welsh actor, writer, comedian, screenwriter, film director, historian, and founder of the Monty Python comedy team Terry Jones (1942–2020) died on January 21 at his home in London.

After graduating from Oxford in the 1960s, Jones started writing for comedy shows, and later formed the group Monty Python’s Flying Circus with John Cleese, Terry Gilliam, Michael Palin, Graham Chapman, and Eric Idle. Their irreverent BBC series, Monty Python’s Flying Circus, ran from 1969 to 1974.

Jones was more than a humorist. He was a chameleon who wrote and performed the troupe’s skits and later directed some of the movies that launched them to international fame, including the classic Life of Brian (1979), a satire about a man who lives next door to Jesus and is misidentified as the Messiah, and The Meaning of Life (1983). Jones also codirected, with Gilliam, Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975), a retelling of the story of King Arthur.

When Jones wasn’t lampooning the medieval world, he was studying it. He was a scholar of medieval history and an expert on Geoffrey Chaucer. He was dedicated to bringing the Middle Ages to contemporary viewers, and won an Emmy for his 2004 BBC series, Terry Jones’ Medieval Lives, in which he debunked stereotypes of stock characters such as the Peasant. Through docudrama-style reenactments and cheery storytelling, visiting farms still run under medieval law and a faux medieval village built by archaeologists, Jones reveals how savvy peasants found ways to revolt, avoid taxes, and move their sons into the clergy to launch them into the intelligentsia.

His antiaristocratic take on history emerged over the "Medieval Lives" series’s eight-episode run— “The ideal of freedom, of owing deference to no one, was a lasting legacy of the medieval peasant,” Jones said. In what appears to be a scholarly companion to the series, Jones and coauthor Alan Ereira skewer monks: they were not just monastic, as it turned out, but richly endowed. Monasteries, according to Jones and Ereira, were “prayer factories” and commercial enterprises. What remained, noted Jones, after the walls of the monasteries and nunneries came tumbling down, was “the powerful sense of social justice that the monastic movement itself taught, that it used to speak out against its own corruption, and that in the end became the weapon that destroyed it.”

The legacy of Jones and the Monty Python troupe is vast. Readers exploring the archives become a kind of Terry Jones of their own, probing what constitutes a life: It is not a single story. Jones worked at the edge of popular culture and current events, and was thus rewarded with more opportunities and an ever-widening audience.

But before his life in books and on television his first audiences were himself, and his parents, whom you can see in the home movies he made using an 8 mm. camera. Here we see the beginnings of a sweet, surprising, and funny experimental presence. Using stop motion, one clip (2:20) features a deck chair that goes for a walk, then a lady deck chair emerges from a shed, sees the male deck chair, and slams the door in its face. It collapses. She lets it in; the camera moves to the sky and lingers there. The door opens and the deck chairs come out with a baby deck chair.

Other home movies reveal ordinary moments with his parents and Monty Python colleagues include playing soccer between takes, having lunch outside, John Cleese pretending to stab him, and a tram ride up a mountain in Canada. At ten minutes, Mr. and Mrs. Jones amble across the yard; his dad gesticulates strangely and his mom grins widely. Jones lets the tree obscure his father, then circles around his parents posing and the camera moves up their bodies, zooming in and out, and pans the sky, like the many longing-filled shots of Italian director Michelangelo Antonioni—a metaphor for wonder and creativity.

Jones tackled his intellectual curiosity from every angle: the speculative Who Murdered Chaucer? A Medieval Mystery, coauthored with four historians, and many children’s books, including Gorillas in our Midst (2015) and The Saga of Erik the Viking (2017). For a small sampling of works examining the contributions of the Monty Python family, see Darl Larsen’s A Book About the Film Monty Python’s Life of Brian: All the References from Assyrians to Zeffirelli (2018), Michael Palin’s Traveling to Work: Diaries 1988-1998 , and Jeff Massey’s Everything I Ever Needed To Know About _____* I Learned from Monty Python: *History, Art, Poetry, Communism, Philosophy, the Media, Birth, Death, Religion, Literature, Latin, Transvestites, Botany, the French, Class Systems, Mythology, Fish Slapping, and Many More!

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!