2018 School Spending Survey Report

Solidarity! Zine Collection Goes to University of Kansas Libraries

Recently more than 1,000 zines from the countercultural Solidarity! Revolutionary Center and Radical Library were acquired by the University of Kansas (KU) Libraries, where they will become part of the Wilcox Collection of Contemporary Political Movements at KU’s Kenneth Spencer Research Library.

Recently more than 1,000 zines from the countercultural Solidarity! Revolutionary Center and Radical Library were acquired by the University of Kansas (KU) Libraries, where they will become part of the Wilcox Collection of Contemporary Political Movements at KU’s Kenneth Spencer Research Library. The Solidarity! collective, which has also been known by other names, including the Mother Earth and Black Cat collectives, since its inception, is an anarchist group that originated in the Lawrence, KS punk scene. Throughout its history it has organized demonstrations, maintained a Food Not Bombs (feeding the homeless) chapter, hosted a women’s health peer education group, and has been involved in other activist projects. According to zine maker Ailecia Ruscin, who worked with Solidarity! in many of its incarnations, and who developed its library and catalog in the early 2000s, the organization was born around the same time that the anti-globalization movement became widely known at the 1999 protests against the World Trade Organization in Seattle. The zine collection is made up of items from Solidarity! members' personal collections, including Ruscin’s, minus the women-authored zines she donated to the Sallie Bingham Center. The Solidarity! Library remains active, free, and open to the public, retaining its circulating book collection of more than 4,000 books on topics such as anarchism, environmentalism, feminism, and vegan cooking at the Ecumenical Campus Ministries in Lawrence. University archivist and curator of the Wilcox Collection Becky Shulte believes the zines are a good fit with the rest of the collection and hopes that, like other holdings in the collection, the material will be used across disciplines, not only political science. Because the library is open to everyone who registers and shows photo identification, not just university students and faculty, the collection is also accessible to people unaffiliated with KU.

Recently more than 1,000 zines from the countercultural Solidarity! Revolutionary Center and Radical Library were acquired by the University of Kansas (KU) Libraries, where they will become part of the Wilcox Collection of Contemporary Political Movements at KU’s Kenneth Spencer Research Library. The Solidarity! collective, which has also been known by other names, including the Mother Earth and Black Cat collectives, since its inception, is an anarchist group that originated in the Lawrence, KS punk scene. Throughout its history it has organized demonstrations, maintained a Food Not Bombs (feeding the homeless) chapter, hosted a women’s health peer education group, and has been involved in other activist projects. According to zine maker Ailecia Ruscin, who worked with Solidarity! in many of its incarnations, and who developed its library and catalog in the early 2000s, the organization was born around the same time that the anti-globalization movement became widely known at the 1999 protests against the World Trade Organization in Seattle. The zine collection is made up of items from Solidarity! members' personal collections, including Ruscin’s, minus the women-authored zines she donated to the Sallie Bingham Center. The Solidarity! Library remains active, free, and open to the public, retaining its circulating book collection of more than 4,000 books on topics such as anarchism, environmentalism, feminism, and vegan cooking at the Ecumenical Campus Ministries in Lawrence. University archivist and curator of the Wilcox Collection Becky Shulte believes the zines are a good fit with the rest of the collection and hopes that, like other holdings in the collection, the material will be used across disciplines, not only political science. Because the library is open to everyone who registers and shows photo identification, not just university students and faculty, the collection is also accessible to people unaffiliated with KU. Augmenting the collection

Schulte has not yet determined how the zines will be described. Her decision, in concert with KU's head of processing, will be informed by other library zine collections. Currently, Schulte reported, she is interested in the University of Iowa's model: "finding aids, grouped thematically." She is not sure yet when the zines will be processed, but is hoping it will be sometime in the next 12 months. Schulte has already begun receiving unsolicited—and sometimes unidentified—donations to augment the Solidarity! holdings, which, she told LJ, makes her happy. She intends to grow the collection by buying zines at the upcoming KC Zine Con and through her regular distributor, Bolerium Books; although the Solidarity! donation didn't come with funding, Schulte has a materials budget for the Wilcox collection. The zines in the Solidarity! collection do not all fall strictly within the Wilcox Collection's parameters of “US left and right wing political literature,” which, according to their website, include student protests, anti-Communist rhetoric, civil rights, race and gender, and other topics. In addition to political zines—Ruscin reports that some of Solidarity!'s primary political concerns were women's health, Anarchist Black Cross (books to political prisoners), permaculture, Food Not Bombs, and Critical Mass (bicycles reclaiming the streets)—there are personal zines and titles in other genres. The zines amassed during the organization's lifespan work as a discrete collection, but Schulte will refine her collection development policy to determine what types of material to add going forward. English professor Frank Farmer, who advocated for bringing the collection to KU, has connections in the zine community, having been engaged in zine scholarship for the last several years, and wants to partner with Schulte on acquisitions.Zines in the classroom

Farmer is also involved with the existing collection. He directs the first- and second-year English program, which for the past three years has included a zine component in first-year courses. Last year over 800 students created and distributed their own zines, along with a paper explaining their design and rhetorical choices. Farmer admits, "More of the zines are about KU basketball than is typical in the zine community at large," but adds that "it was important to us that we not put any restrictions on the topics students chose for their zines." Schulte will consider adding these student-created zines as a separate collection. Farmer uses zine examples in his classes, and teaches other professors in the program—many of them first-time teachers—about zines. In a video about the collection created by KU News Service, Farmer called zines an "Index to a certain history" that affirms "particular values and perspectives that we don't ordinarily see in mainstream discourse." Ruscin agreed, stating that, "Culture needs to be documented, [a] moment of resistance that needs to be recorded." She said that she would consider donating her papers (fliers, pamphlets, zine flats, postcards, meeting notes, buttons, mission statements, reading notes for reading and study groups, email lists, and organizational notes) from her time with Solidarity! to the Wilcox Collection, but they might also go to Sallie Bingham, to complement her zines held there. As excited as Farmer is about working with zines and having them in one of his university libraries, he told LJ, he worries about the effect scholarship has on zines, and wonders if he might be contributing to their demise or whether he is appropriating zine culture in ways that do it harm. Farmer's concern is much appreciated by members of the community, but zines have been the topic of research for many years and are still thriving. However, some zine makers have refused researcher requests to write about their work.Intellectual property

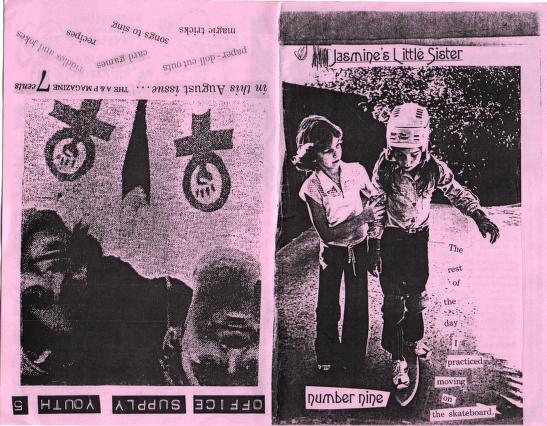

"Jasmine's Little Sister #9 / Office Supply Youth #5" by Ocean Capewell / Kimberly Mitchell from Solidarity! collection

Other zine makers welcome it. Social worker and author Ocean Capewell has a zine in the collection, Jasmine's Little Sister #9, a split zine with Office Supply Youth #5, by Kimberly Mitchell, which Capewell wrote in 1997 when she was in her early teens. The zine was digitized without the authors' knowledge, along with 833 others from the Solidarity! collection that can now be found at the Internet Archive. When this was brought to her attention on Facebook, Capewell responded, "No, they didn't ask me. But I don't really mind." She went on, "I have an unusually chill relationship with my past zines. Most people haaaate [theirs] and I think of them as interesting little tiny capsules." Capewell and her coauthor may be in the minority of zine creators who don't mind having their work scanned and made available without their permission. Regardless of the author’s attitude, zines are protected by copyright unless they contain explicit anti-copyright statements, though that does not protect them from the Internet Archive's opt-out approach. Solidarity! member Sarah Madden, who digitized the zines—one milk crate–full at a time with an 11” consumer scanner that could only accommodate ten pages without jamming—was motivated by the fear that the zines would be lost forever. Madden is the daughter of a historian. When Solidarity! lost its lease, and the zines were shuttled from space to space, including a collective house that was on the market and a storage unit, she told LJ, she thought, "I don't want [these zines] to disappear on my watch." Ruscin was critical of mass zine digitization, pointing out that archiving zines online could be a particular concern for people's whose gender expression has changed since the zine’s creation, perhaps having written it under a now dead name. She is in favor of zines being held in libraries, even under third-party donations, but thinks that digitizing them without consent is problematic. Madden doesn’t disagree. Now that the zines have found a safe home, she is considering removing the zines from the Internet Archive and restoring them as permission is granted.Community concerns

In the zine librarian community, ethics are as important as legal concerns, as evidenced in the collectively created Zine Librarians Code of Ethics. Schulte has no plans to digitize items from the Solidarity! collection. She noted that Wilcox "has many items that we would like to digitize but don’t have permission for.” Sometimes local activist populations have negative feelings about higher education. Ruscin related that some Solidarity! members had anti-student and anti-school sentiments. They had a "Skip the tuition money; learn on your own" philosophy in line with their critique of capitalism, she said. Ruscin herself, who did not share this view, was a graduate student during much of her time with Solidarity!. She has since left academia but remains an activist, and is happy that the collection is with KU because, she said, "it is great for it to be preserved."

RECOMMENDED

TECHNOLOGY

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!